Time Management Didn't Work

“The problem with self-improvement is knowing when to quit.”

— David Lee Roth, Inductee, Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

The size of the self-improvement market is staggering, reaching $13.4B in 2022. One major component of this self-improvement market is the set of books and online courses about time management that promise consumers better productivity and a more balanced life. Entrepreneur magazine listed the top time management and productivity books of all time. As a former startup tech exec, always trying to do more, I have read many of them. The tl;dr on all this is that I grew skeptical that any of these books or techniques could provide a set of answers to better productivity and a more balanced life that applied to my situation during my career. I think this quest led me to another answer — retirement.

One problematic example

To be sure, there are definitely good ideas in all of the books I’ve read that shed light on what many others do to seek more productivity and life balance. They present alternative ideas, but I was unable to apply many of them to my own situation as a startup tech exec.

Take the first book on that list in Entrepreneur titled The 7 Habits for Highly Effective People. Habit #3 in that book is “Put First Things First.” Stephen Covey describes why some people’s habits of managing themselves to a to-do list just doesn’t work. The problem is that traditional to-do lists don’t differentiate between urgent and important tasks. As such, following a to-do list can result in focusing on urgent but less important tasks, neglecting those that are crucial for long-term success.

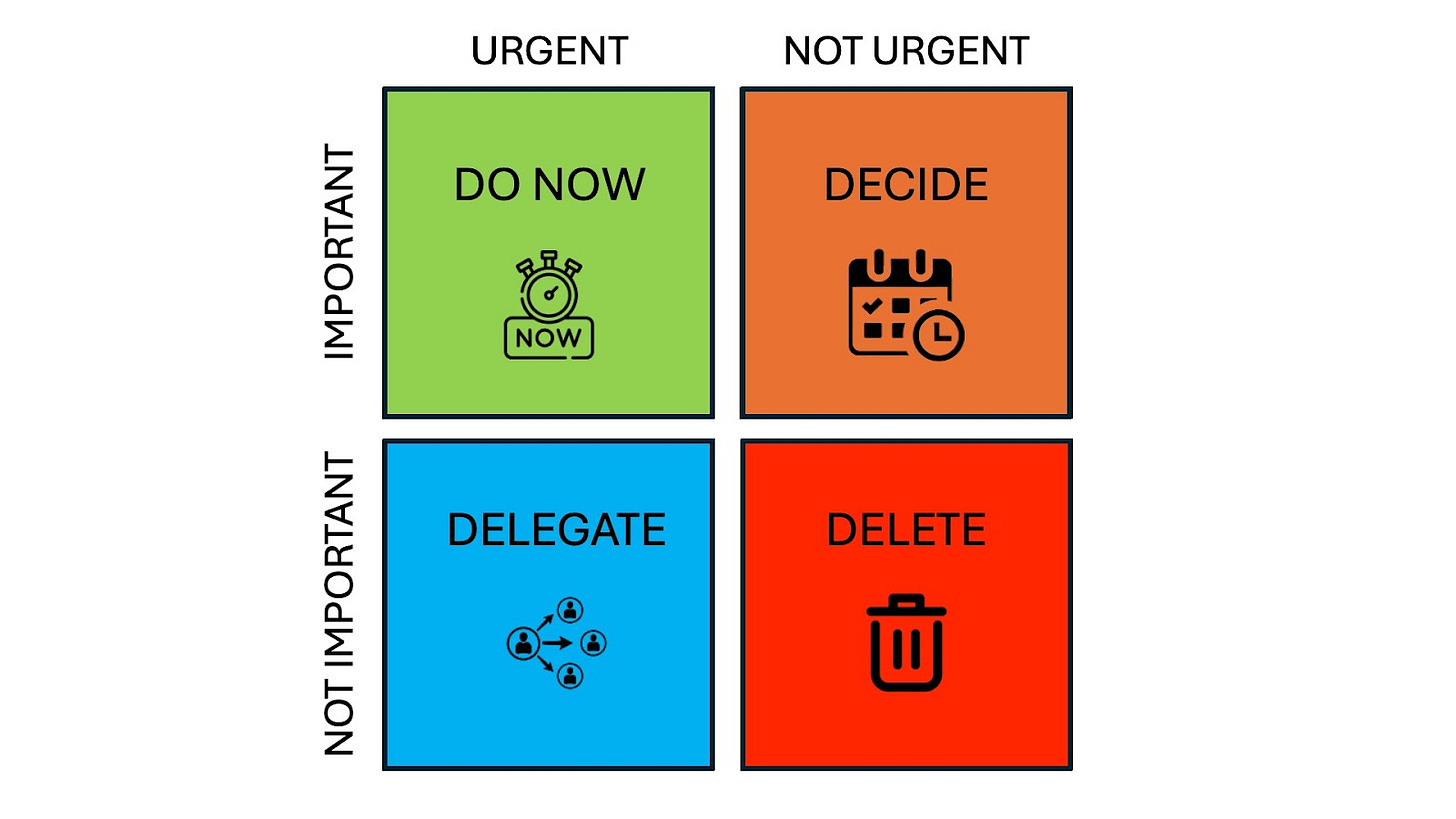

In response, Covey describes the Eisenhower Matrix. (I referred to this tool in my earlier post “Repairing Damage in Retirement.”)

On one axis is the urgent, and on the other axis is the important. The concept is that for the really urgent AND important tasks, you have to just do them (green). For the tasks that are not urgent and not important, you delete them (red). For the urgent but not important tasks, you delegate them (blue). And for the important and not urgent tasks, you DECIDE to do them by planning and scheduling (orange). For example, having dinner with your family at night is a task that you should simply DECIDE to do (orange). Logical, right?

Even though this approach is logical. I personally found the advice hard to follow in my own situation.

No one to delegate to. The Eisenhower matrix suggests that the correct thing to do for “the urgent and not important” is to delegate (blue). In the real world of an early stage company, there’s often no one to delegate to. Some of the reason is that startup companies might be too cash constrained to hire people. However, this isn’t the whole story. Even when the money exists because of venture capital or other good fortune, it’s often just not the right answer to have too many people around before a company has achieved true product-market fit. (This could be the subject of a whole other blog article if readers are interested in this one…)

Too many urgent items to do now. The matrix suggests that the correct thing to do for the “urgent and important” is to do them now (green). In the real world of an early stage company, there might be simply too many of these to manage in a typical workday or even in an extended “after-hours” workday.

Decision Fatigue. The matrix suggests that the correct thing to do for the “not urgent and important’ is to decide (orange). The problem is that we all get decision fatigue. I’ve seen some versions of the Eisenhower Matrix replacing the word “Decide” with “Schedule.” Unfortunately, the calendar of a startup tech exec can often be really full already!

Items to delete turn out to be more important than you think. The seemingly obvious is that the matrix suggests that the correct thing to do for the “not urgent and not important” is to delete (red). However, in retirement as I reflect back, it’s often the things that are least “important” for a company’s mission, goals, or objectives that turn out to be things that people remember most. I’ve mentioned before how I’m probably more remembered by former colleagues for rap songs or karaoke than any of the business or product plans I put together.

I later found that the problems with this decision framework are not constrained to just the world of a startup tech exec. Just do a Google search on “Why the Eisenhower Matrix doesn’t work”, and there are pages of results written from many different viewpoints other than mine, with even a cool “experimental” explanation by Generative AI.

So, to-do lists suck, and the Eisenhower Matrix sucks. What next?

There are more questions

I have found that time management techniques offered in other books can also conflict with one another.

25 minutes or 4 hours of focus time?. The Pomodoro Technique advocates for improving focus and motivation while reducing distractions and burnout by splitting work into 25 minute intervals followed by breaks. On the other hand, Cal Newport’s book (listed as #7 on the Entrepreneur list) advocates for deep work with periods of 3-4 hours per day for sustained, high intensity focus without distractions. So which one of these options is best?

Categorize all tasks, or just one (your “frog”)? David Allen's Getting Things Done (#6 on the Entrepreneur list) motivated me to buy an app called OmniFocus back in the day. The concept was to reduce stress by capturing everything, determining the next action, and then categorizing each item based on context (like @Office, @Errands, @Calls, @Anywhere, @Agendas with specific people or meetings). Ultimately, I gave it up because it took so much discipline to process every task in its appropriate context. On the other hand, Eat that Frog (#3 on the Entrepreneur list) is a much simpler idea. Rather than categorizing everything, it advocates to identify, at the end of each day, the most important thing to work on the next day (your “frog”). The concept is that by taking on the most important task of the day, it isn’t just about prioritization but also about creating a sense of accomplishment and momentum to give the positive energy to tackle other important tasks. So should we reduce stress by capturing everything or by focusing on just one thing?

Of course, these books aren’t totally wrong. Success of any specific advice simply depends on both the individual and the roles they’re in. Pomodoro likely works well for simpler types of tasks, and Deep Work likely works well for more complex work. Getting Things Done likely works for very activity-oriented jobs with many contexts, and Eat that Frog may work well for more strategic roles. While good ideas were presented by these books, none seemed to quite fit for me or my situation.

Summing it up differently

For me, the takeaways really came from books like the 4 Hour Workweek (#4 on the Entrepreneur list) by Tim Ferris. Ferris talks about the “DEAL” where you Define what you want, Eliminate the tasks that don’t help with that, Automate remaining tasks through outsourcing and technology, and then Liberate yourself by working remotely and taking little mini-retirements along the way.

There are two ways to look at Ferris’ work. One way is to simply dismiss the specific recommendations in the book and think “well, I guess this is good for you, Tim”. After all, the culture of most Silicon Valley tech startups often doesn’t allow for the executives to eliminate tasks like meetings, reading email and Slack, or liberating oneself from traditional work hours. In general, doing a good job and leading teams requires that the executives are highly present and available for their teams and other executives. Simply not answering one’s email and Slack messages or attending meetings is not generally part of a typical success formula for most. Of course, Elon Musk provides an extreme example of breaking this mold by somehow floating between multiple companies while playing a major role in the last Presidential campaign!

So the way I ultimately looked at Ferris’ work was to figure out how to break the mold. By more carefully “Defining” what I wanted in this phase of life, it became easier to “Eliminate” the tasks that didn’t help me get there. While the culture of many startups requires that the executives overwhelm themselves with many of those tasks (meetings, email, Slack, etc.), the cultures often do not require these tasks of consultants. So, the way of achieving the 4 Hour Workweek for me was semi-retirement.

To sum it up, I think of the following saying:

The trouble with the rat race is that even if you win, you’re still a rat.

— Lily Tomlin

For me, the ultimate time management and life balance hack was to leave the rat race. I’m not trying to claim that everyone can or should do this. I’m just admitting that I wasn’t easily able to find an answer to productivity and life balance during my career because I didn’t find that my career choice made it easy to do so at the time. And I am now “repairing damage” as I wrote earlier.

Have you found a better time management hack?