“Diversification is always an apology.”

— Andy Goldberg, former Global Head of Market Strategy for JPMorgan Private Bank

I was recently asked by a friend over beers how I think about savings and investment in retirement. I have shifted my views here given some experiences, and the quotation above is one I heard at a luncheon hosted at the Four Seasons in Seattle right before retiring.

The view expressed here is that when properly managing risk in a portfolio, there will always be parts of the portfolio that are sucking. The aim, in this case, is to have investments that aren’t positively correlated. To prevent having a portfolio where everything goes down at the same time, it’s impossible to have a portfolio where everything goes up at the same time — creating a situation where there will always be parts of the portfolio that drag down total returns.

Warren Buffet has stated that an oft-quoted text, The Intelligent Investor (1949), was “by far, the best book on investing ever written.” In that book its author wrote the following:

“The essence of investment management is the management of risks, not the management of returns"

— Benjamin Graham

So what special risks are there early in retirement? I’ll talk about three that we have lived through: sequence risk, inflation risk, and interest rate risk. The combination of these three factors did evolve my thinking of savings and investment. And it made me realize that I need to get in the mode of apologizing to myself and to welcome parts of the portfolio that might suck to manage risk.

Sequence Risk

Stocks are a long-term growth engine. Few would debate this point.

Still, the biggest risk we have seen in our lives is associated with stock market downturns in the early period of retirement while withdrawing from a portfolio. I had friends who had retired both during the dot-com crash and the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) who were permanently impacted. The problem is associated with the need to sell assets while the market is down for a long period of time. This need to withdraw could have the impact of either leaving fewer assets to recover when the market rebounds or to require significant changes in retirement planning.

For those who don’t remember the dot-com crash, it’s important to remember that this was a period when the NASDAQ Composite index lost 75% of its value. It took about 15 years to return to its peak, during which any retiree was withdrawing 15 years of living expenses at reduced values, leaving fewer assets to recover even as the market rebounded.

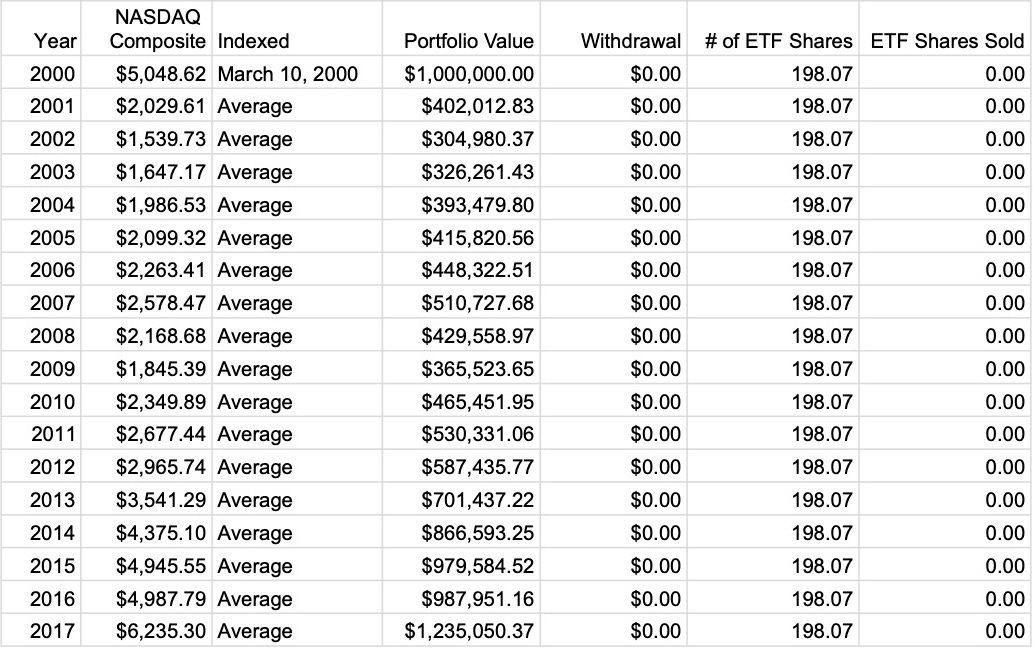

Those of us who did not retire and who kept earning income through the dot-com crash and GFC survived well because we didn’t need to withdraw during the period. Imagine having $1M invested in the NASDAQ Composite index in the year 2000. For this analysis, I’m using a fictitious scenario with an ETF (exchange traded fund) indexed on the NASDAQ Composite where the initial valuation was at the NASDAQ Composite peak on March 10, 2000.

Scenario 1: No withdrawals

With no withdrawals and keeping the money invested in the NASDAQ Composite, a person working through the whole period would be back ahead and moving forward with a positive portfolio value above the $1M by 2017.

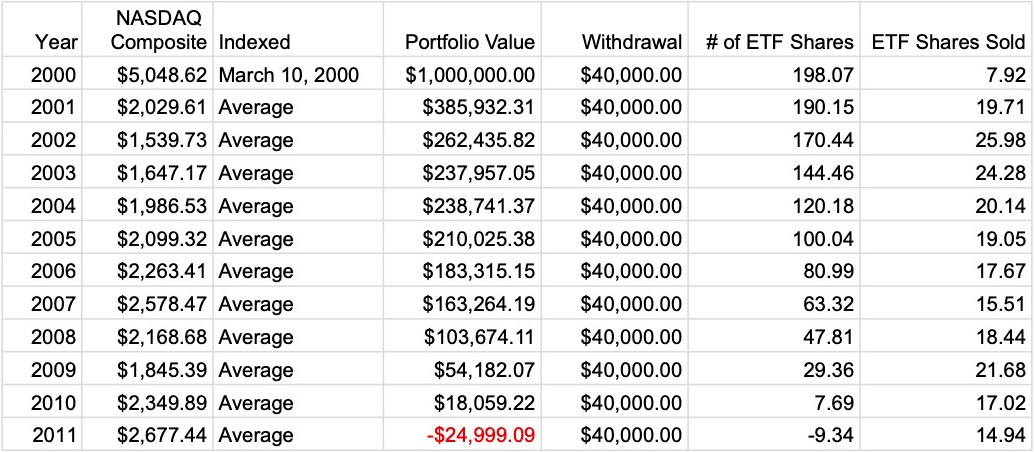

Scenario 2: Fixed $40,000 Withdrawals

However, imagine if a retiree made the decision to retire on March 10, 2000 at the market’s peak, with the plan of withdrawing $40,000 per year (4% of the original portfolio). The ETF shares purchased in the year 2000 lost significant value and shares had to be sold at that lower value. In this case, the retirement plan would have failed entirely in 2011 because the needed withdrawals would have exceeded the portfolio value at that time.

FAIL!

Scenario 3: Withdrawals at 4% of Portfolio Value

Of course, the savvy follower of the 4% rule knows that the 4% rule is against the portfolio value, not a fixed amount. So, in this case, the retiree would have to downscale their lifestyle significantly from an initially assumed $40,000 draw at the time of retirement to much lower values, with a trough of $10,125.50 in 2009 during the GFC.

To weather most short-duration market downturns, financial planners generally recommend maintaining a cash reserve so that assets don’t need to be sold during market lows.

What about for longer term market downturns?

Inflation Risk

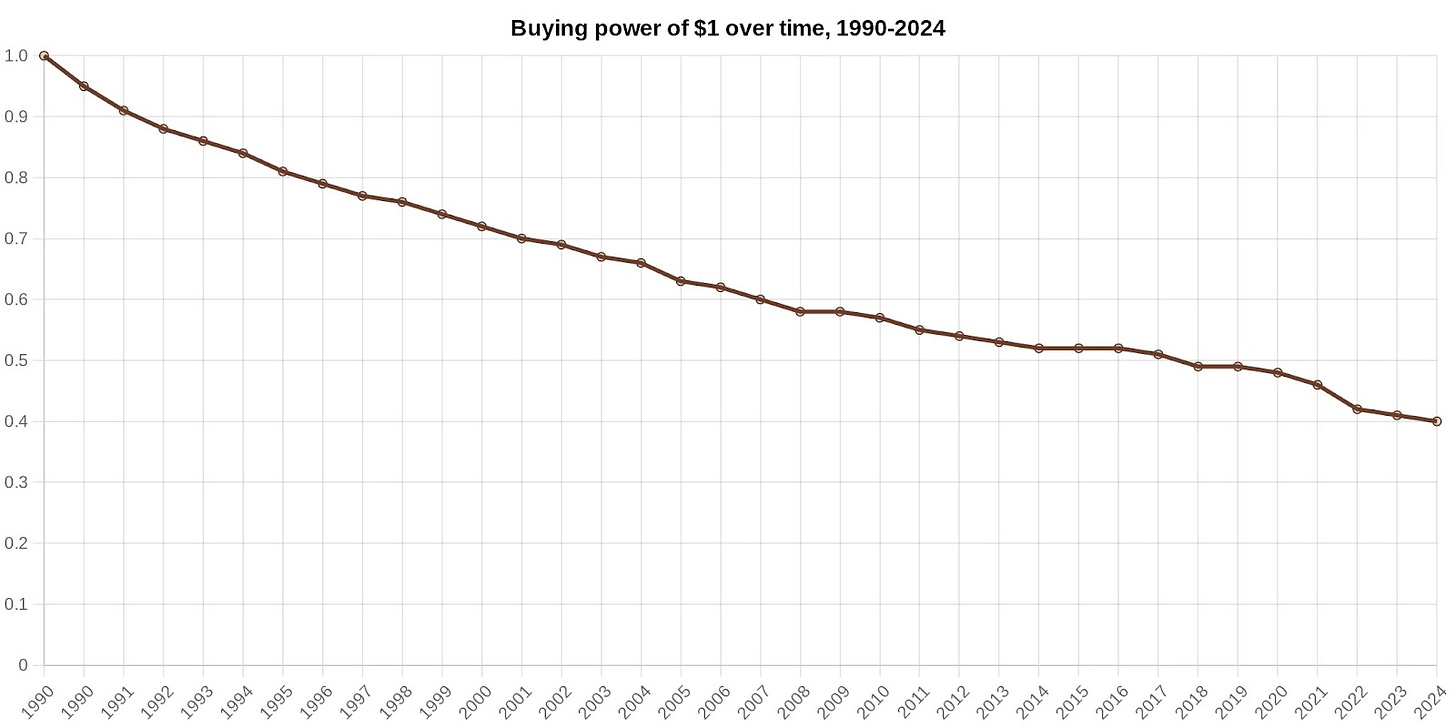

So, why not take this advice to the extreme and just maintain a much larger cash reserve to weather a market like 2001-2016? Why do people take these risks with the stock market in retirement to begin with? The problem is that inflation eats into retirement, too. I graduated with my master’s degree in 1990. Back then, $1 in 1990 was equivalent to about $2.41 today.

The impact for a retiree is that the buying power of any dollar stuffed into a piggy bank in 1990 would provide only 41.4 cents of equivalent buying power 34 years later. While 34 years is a long time, it’s basically the equivalent of an early retirement period, going from age 51 to 85. The problem with Scenario 2 above with fixed $40,000 withdrawals is that the living standard would be significantly lower at the end of retirement than at the beginning.

Source: CPI Inflation Calculator

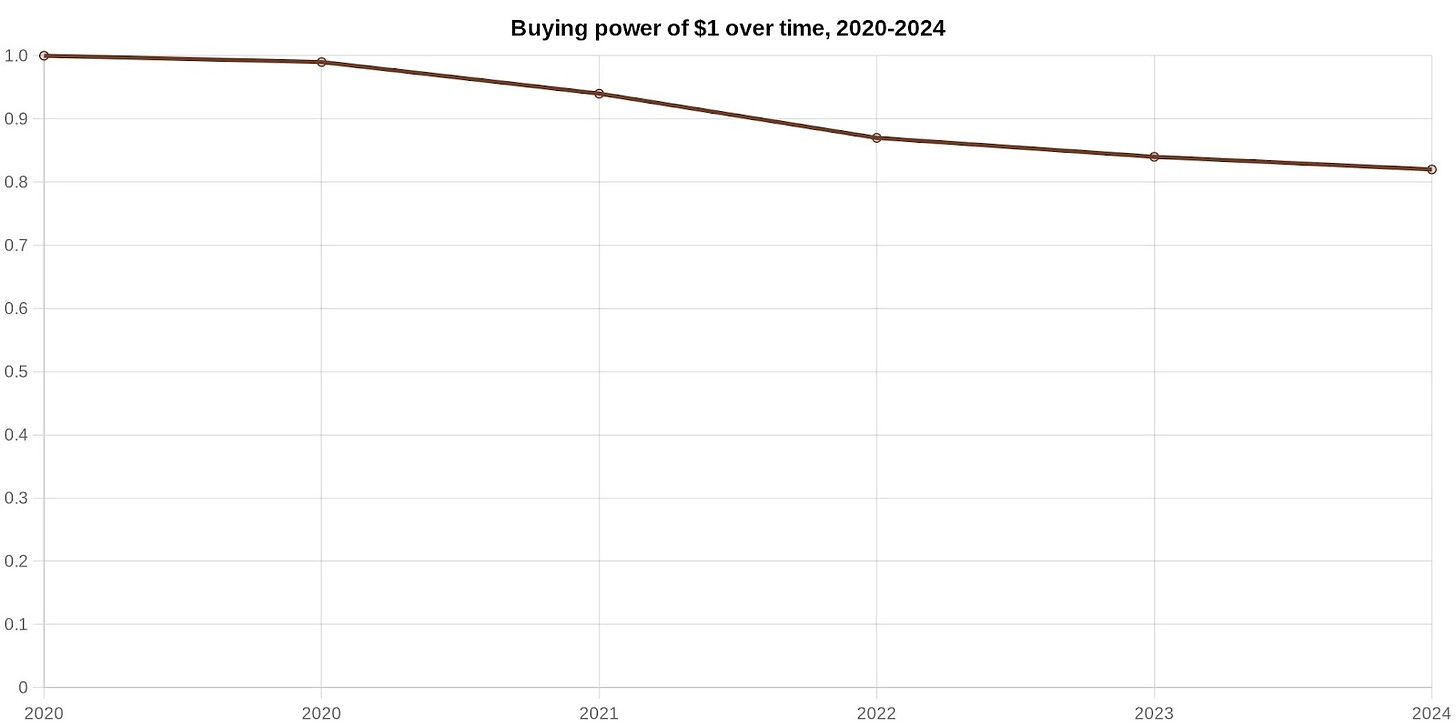

This effect has been particularly pronounced in the aftermath of COVID, as $1 in 2020 is the equivalent of $1.22 today. In other words, $1 stuffed into a piggy bank in 2020 only had the equivalent of 82 cents of equivalent buyer power just 4 years later!

Source: CPI Inflation Calculator

As such, maintaining stocks in a portfolio is generally recommended by financial professionals as a way to fight inflation.

However, to manage sequence risk and to weather longer market downturns without selling at low stock prices, most financial professionals recommend a diversification of stocks with bonds. Even though bonds don’t generally provide the returns of stocks, the last twenty years demonstrated that movements in bond prices don’t generally correlate positively with movements in stock prices. As such, the thought is that when stocks are down, bonds generally are not.

The logic is that during a recession, when stocks are typically low, the Fed will cut interest rates to stimulate the economy. In general, lower interest rates result in higher bond prices. Likewise, when the economy is hot and there is a risk of inflation — conditions in which the stock market tends to be up — the Fed will raise interest rates to cool the economy. In general, rising interest rates result in lower bond prices. So the price correlation over the last twenty years has been negative. Low stock prices correlate with high bond prices and vice versa.

The theory is that a retiree can weather through longer stock market downturns with bonds and without selling stocks at low points and without significantly reducing the asset base for recoveries.

So what’s the problem?

Interest Rate Risk

2022 was a stark demonstration of the problem of significant interest rate hikes, particularly in a period of simultaneously high inflation.

In 2022, the larger theory was that inflation was caused by supply chain disruptions, not strictly consumer demand. As such, there was a period where the Fed had raised the federal funds rate by 4.25 percentage points, disrupting economic activity and causing higher unemployment, but without lowering inflation. Supply chain disruptions and their after-effects kept inflation at an average of 8.0 percent in 2022, up from an inflation rate of 4.7 percent in 2021. This put both the stock market and the bond markets in turmoil.

The NASDAQ Composite was down 33.1% in 2022. This happens. The NASDAQ Composite was previously down 40.45% in 2008, 31.53% in 2002, 21.05% in 2001, and 39.29% in 2000. (source:Wikipedia) For those early in retirement, these kinds of down markets presented the sequence risk mentioned above.

What is unique about 2022 in my lifetime was that bonds weren’t there to pick up the slack. In fact, 2022 was the worst year for bonds in 250 years. For example, the longest 30-year US government bonds lost 39.2% in 2022, setting a record dating back to the year 1754!

This drop in the bond market as a whole was largely attributed to the sudden raising of the federal funds rate from near-zero levels to 4.25 percent in an attempt to fight inflation. History has shown that inflation did come down, and as I’m writing this in October 2024, the economy appears to be nearing the Fed’s target 2 percent inflation rate. However, that wasn’t the case in 2022.

So, despite the wisdom of the 60/40 portfolio (60 percent stocks, 40 percent bonds) recommended by many financial professionals, 2022 turned out to be a bad year, with the Morningstar Global 60/40 index down 17.73 percent in 2022, caused by the simultaneous drops in both the stock and bond markets. Now that we’ve seen this happen, we know it can happen again.

What now?

So, at this phase in my retirement, I know too much reliance on stocks creates sequence risk. Holding on to too much cash creates inflation risk. A traditional 60/40 diversified portfolio does not insulate against situations like 2022 when both interest rates and inflation are high. And I’ve experienced all of these situations now. My current belief is that a single strategy doesn’t work, and diversification (and apologizing) are a key part of going forward in retirement.

This is an ongoing exploration for me, and I can continue to write on topics associated with this journey. I’ve implemented a loose “bucket” strategy where there are pools of money assigned to different investment strategies (mainstream growth, mixed, alternatives / private equity, cash), as well as the usage of a credit line for direct private lending. Of course, supplementing with income in semi-retirement is also a part of this strategy, too. If you’re at all interested, I can write more on all of this retirement financial stuff to share knowledge in the B-sides of this Substack. Just let me know!

Thanks for this post Steve. And so glad to see The Intelligent Investor made an appearance which as you know was required reading in my family!

I appreciate the analysis of the past few decades which was eye opening. A few other thoughts from my end in reading this.

First, I completely agree that you have to be flexible in portfolio management. Diversification also applies to having multiple managers if you have enough assets to merit that. Even in a household that managers their investments themselves, they likely have mutual or similar funds in their portfolio so they have indirect managers of their assets. It might be better to have 50% of an investment type - say US Large Cap - at two different groups with the same target list.

Second, there is another situation that I am thinking of semi-retired. In this situation, the family still has one or both of the couple working. At least one of them has health coverage (this is pre-Medicare) and their combined salary, while likely decent by most standards is not enough to cover their annual cash flow needs. So, they are working off investment income (ideally not invading capital while they are working) plus their salaries. This situation might change how they view risk but is also a step towards planning for retirement too. Almost a trial period. Maybe they only work part-time or are working in a field that they are passionate about but is not necessarily highly compensating (such as non-profit or teaching).

Third is the concept of estate planning which applies to those working, retired or my new term of semi-retired. Assuming the family has enough assets to considering leaving a legacy to their kids or other loved ones, how much do they want to leave? Maybe there are other issues to consider? For example, my niece has a congenital health concern, so my sister-in-law has to approach her planning thinking of how her daughter will have enough funds after my sister-in-law is gone. In other cases, there can be just the desire to provide some funds to their descendants because they want to. With hopefully longer and longer lifespans, this gets more complicated, particularly as healthcare costs are likely to rise in one’s 80s and 90s if blessed to live that long.